Setup of the dataforest network (short version)

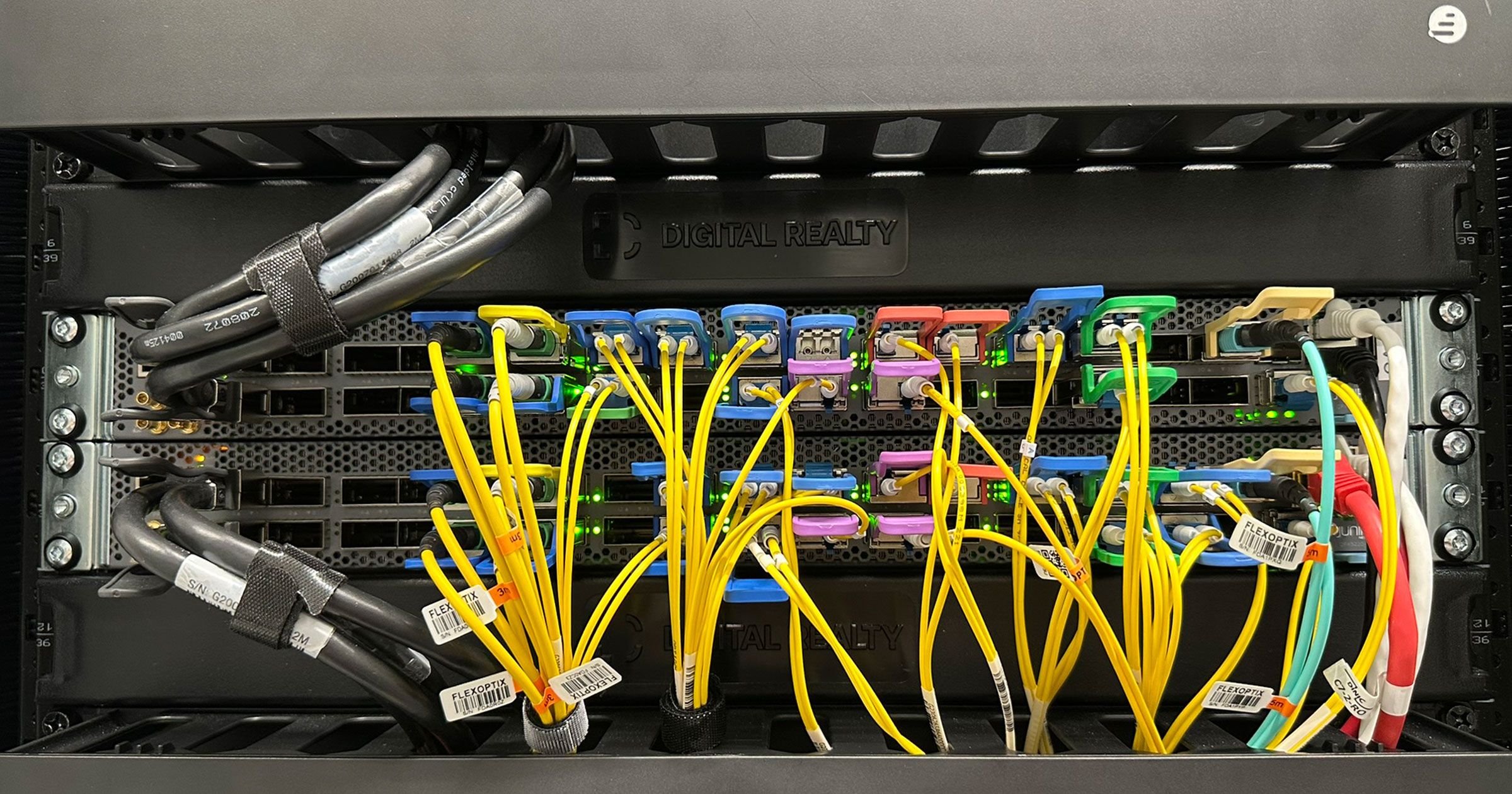

We operate several locations within Frankfurt, connect them with our own fiber optic lines and (so far) let everything converge on the Interxion campus (now actually Digital Realty), where we operate our central edge routing and filter DDoS attacks. There, we connect several carriers and numerous peerings. We peer both via public Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) such as DE-CIX with many other network operators, as well as via so-called private network interconnects (PNIs) with networks with which we exchange a particularly large amount of traffic. Google and Cloudflare are examples of this. In addition to several Juniper MX routers, our aggregation switches play a central role, because they connect all components of our network internally and externally.

We started planning the network in its current form almost three years ago and started implementing it two and a half years ago. At the time, we affectionately called the project "terabit backbone" (which quickly became an understatement). Juniper QFX5220-32CD was chosen as aggregation switches because they offer 32x 400G per device and it was clear to us that we wanted to implement our new network concept with 400G technology in order to be ready for the future. Although we have only been using Arista in core switching for our server landscape for over five years, which are ahead in terms of price/performance in terms of 40G and 100G and are really exceptionally stable, 400G switches were needed for our new PoP, and the availability of these was significantly better at Juniper back then.

Of course, even then it was clear that we wanted to operate a network (as before, only limited to one data center back then) that was designed for high availability, i.e. did not contain any central components in the core and edge areas whose failure or defect could end disastrously. And the redundancy concept works too — we've never had a hardware-related failure since running our own AS58212. Unfortunately, the hardware is only one aspect of many and there are a thousand ways to tear down the network — on the said 23.10.2025, we "successfully" took one of these paths. More about that in a minute.

There are two options when combining multiple Juniper switches into a highly available device network, and many manufacturers offer very comparable options. The first, probably the most common and well-known at Juniper, is a so-called Virtual Chassis (VC). Here, a primary switch takes on the role of control plane including management (SSH) and the other devices in the network are controlled via this, meaning that they themselves can no longer be "managed" via SSH. The config comes entirely from the primary switch. If this fails on the hardware side, this is typically no problem for a VC — another switch takes on the role of "boss" and packet forwarding simply continues after a few seconds. However, when a software error occurs, the VC can lie on its nose in such a way that nothing works without "power out and back in again." We had annoying experiences with this a good six to seven years ago and were reluctant to repeat them.

Unsurprisingly, we therefore did not form a VC from our aggregation switches. Instead, the switches were connected together via MC-LAG. MC-LAG is conceptually different: Here, both switches remain independent devices with their own control plane, management and software. They are only linked so that connected "clients" (primarily routers and DDoS filters in our case) see their links as a single LACP channel and can use all links "Active/Active". The Inter-Chassis Control Protocol (ICCP) runs between the devices, synchronizing the status of the links and forwarding information — without "merging" the whole thing into a single chassis. The big advantage: If the software on one of the two switches crashes or behaves strangely, the second is less affected in case of doubt because it keeps its own process environment and can continue working independently. If the MC-LAG gets into a split-brain situation (which is very unlikely with our redundant ICCP link plus configured fallback via the management network), it is clearly regulated how the devices behave and what happens. In return, the setup is more complex, is individual for each LACP channel and each configuration must be made individually on each device.

Timeline of the outage

1:26:05 p.m.: We commit the following configuration on both switches:

[edit interfaces irb]

+ unit 97 {

+ family inet {

+ address 10.97.2.2/29;

+ }

+ }

[edit vlans vlan-97]

+ l3-interface irb.97;

+ mcae-mac-synchronize;

1:26:21 p.m.: The "Layer 2 Address Learning Daemon" says its farewell; due to the bug on both switches at the same time:

(Original edition abbreviated to include redundant messages and limited to one of the devices)

Oct 23 13:26:07 ca2.ix-fra8 audit [15352]: ANOM_ABEND auid=4294967295 uid=0 ses=4294967295 pid=15352 comm="l2ald" exe=" /usr/sbin/l2ald" sig=6 res=1

Oct 23 13:26:11 ca2.ix-fra8 systemd [1]: l2ald.service: Main process exited, code=dumped, status=6/abrt

Oct 23 13:26:35 ca2.ix-fra8 audit [17874]: ANOM_ABEND auid=4294967295 uid=0 gid=0 ses=4294967295 pid=17874 comm="l2ald" exe=" /usr/sbin/l2ald" sig=6 res=1

Oct 23 13:27:13 ca2.ix-fra8 audit [21210]: ANOM_ABEND auid=4294967295 uid=0 ses=4294967295 pid=21210 comm="l2ald" exe=" /usr/sbin/l2ald" sig=6 res=1

Oct 23 13:27:41 ca2.ix-fra8 audit [22866]: ANOM_ABEND auid=4294967295 uid=0 ses=4294967295 pid=22866 comm="l2ald" exe=" /usr/sbin/l2ald" sig=6 res=1

Oct 23 13:27:45 ca2.ix-fra8 systemd [1]: l2ald.service: Main process exited, code=dumped, status=6/abrt

Oct 23 13:27:45 ca2.ix-fra8 systemd [1]: l2ald.service: Start request repeated too quickly.

Oct 23 13:27:45 ca2.ix-fra8 systemd [1]: Failed to start "Layer 2 Address Flooding and Learning Daemon on RE."

Oct 23 13:27:45 ca2.ix-fra8 sysman [9242]: SYSTEM_APP_FAILED_EVENT: App has failed re0-l2ald

Oct 23 13:27:45 ca2.ix-fra8 emfd-fpa [11097]: EMF_EVO_ALARM_SET: Alarm set: APP color=red, class=chassis, reason=Application l2ald fail on node Re0

It should be noted here that the process only stayed offline for ca2. On ca1 the process came back after several identical crashes. Ultimately, this did not help, because the error pattern meant that both devices were affected in the end.

1:31:29 p.m.:

Our monitoring system Observium sends alerts about ca2.ix-fra8 to the on-call engineer, as its chassis reports a "red" alarm, which is also acknowledged at 1:31 p.m. When the colleague is on the computer at 1:33 p.m., the outage is already known and the "red" alarm is not passed on to the network department, which later turns out to be an error. More about this in the action plan below.

1:33:08 p.m.:

At least switch ca2 loses its MAC table because the (crashed) l2ald can no longer keep it up to date. As a first step, it breaks down the inter-chassis link of the MC-LAG. At least on this, both devices are absolutely in agreement.

Oct 23 13:33:08 ca1.ix-fra8 bfdd [11707]: BFDD_STATE_UP_TO_DOWN: BFD Session 10.50.1.2 (IFL 0) State Up -> Down LD/RD (16/16) Up time:38w6d 07:42 Local Diag: ctlExpire Remote Diag: None Reason: Detect Timer Expiry.

Oct 23 13:33:08 ca2.ix-fra8 bfdd [11793]: BFDD_TRAP_MHOP_STATE_DOWN: local discriminator: 16, new state: down, peer addr: 10.50.1.1

That alone wouldn't have been too big an issue, but the problem is deeper: Learning MAC addresses no longer works. We assume — with near certainty — that this is why the fallback via the management network, through which the switches could still have been reached (and should be able to be reached according to the configuration), does not work. In any case, the ICCP is down, shows our live debugging a few minutes later, and can no longer be easily obtained online — no matter via which link.

Due to the undefined state (split brain), all LACP channels fly apart and the connectivity of our routers is immediately gone:

Oct 23 13:33:08 ca1.ix-fra8 lacpd[11741]: LACP_INTF_MUX_STATE_CHANGED: ae10: et-0/0/8:0: Lacp state changed from COLLECTING_DISTRIBUTING to DETACHED, actor port state : |-|-|-|-|OUT_OF_SYNC|AGG|SHORT|ACT|, partner port state : |-|-|DIS|COL|IN_SYNC|AGG|SHORT|ACT|

[...]

Oct 23 13:33:08 ca1.ix-fra8 lacpd[11741]: LACP_INTF_MUX_STATE_CHANGED: ae10: et-0/0/10:3: Lacp state changed from COLLECTING_DISTRIBUTING to DETACHED, actor port state : |-|-|-|-|OUT_OF_SYNC|AGG|SHORT|ACT|, partner port state : |-|-|DIS|COL|IN_SYNC|AGG|SHORT|ACT|

In such a split-brain situation — which should never happen — this is not misconduct, but to be expected, "works as designed": If the ICCP is gone but both switches are still up, they do not identify themselves to connected devices as a joint LACP partner anymore. Technically, it works like this: In normal conditions, both switches send the same system ID (say 00:00:00:00:00:10), which we have set in the configuration — unique for each LACP channel. The other side therefore sees: All ports are "in agreement" and may become part of the LACP channel — all is well. But now we are no longer in normal state — and both stop using the configured shared system ID 00:00:00:00:00:10 and fall back to their local default system ID. Connected devices then see two different LACP partners and only add one of them to the LACP channel. Its system ID is also adopted by connected devices for the respective LACP. The logical interface must flap — so far, so normal. And we can also understand this on a router connected there:

Oct 23 13:33:10 re0-mx10003.ix-fra8 lacpd[12200]: LACP_INTF_MUX_STATE_CHANGED: ae0: et-1/1/9: Lacp state changed from WAITING to ATTACHED, actor port state : |-|-|-|-|IN_SYNC|AGG|SHORT|ACT|, partner port state : |-|-|-|-|IN_SYNC|AGG|SHORT|ACT|

[...]

Oct 23 13:33:10 re0-mx10003.ix-fra8 lacpd[12200]: LACP_INTF_MUX_STATE_CHANGED: ae0: et-0/1/0: Lacp state changed from WAITING to ATTACHED, actor port state : |-|-|-|-|IN_SYNC|AGG|SHORT|ACT|, partner port state : |-|-|-|-|IN_SYNC|AGG|SHORT|ACT|

Exactly half of the links (from the still working switch) came back to ae0, this resolved the split-brain situation.

The expected behavior would have been for the network to simply continue running at half capacity on one of the switches. Although this would have caused an outage, it would also have led to automatic recovery after a few minutes, as "only" all internal and external BGP and OSPF sessions would have had to be rebuilt.

We know why this didn't work. More about that later — continue in the timeline.

1:33:08 p.m.:

Our monitoring system reports the unavailability of all routers to both the on-call staff and the network department. The outage is directly linked to the modified configuration, even though the cause is unclear. The suspicion (which is later confirmed) is not that there is a faulty configuration, but rather some kind of Junos bug.

1:33:36 — 1:34:00 p.m.:

We roll back the last configuration.

Oct 23 13:33:36 ca1.ix-fra8 mgd[29499]: UI_LOAD_EVENT: User 'root' is performing a 'rollback 1'

Oct 23 13:33:43 ca2.ix-fra8 mgd[7077]: UI_LOAD_EVENT: User 'root' is performing a 'rollback 1'

Since all LACP channels are coming back up after the (largely expected) flap, we initially assume that the network should now recover. Contrary to expectations, however, this does not happen; on the contrary: Our monitoring reports all BGP sessions as down after a few minutes.

1:35:04 p.m.:

We communicate the fault via our status page, which we still recommend subscribing to.

1:36 p.m.:

We call all available employees, including those from other departments, to the support hotline so that we can answer as many calls as possible. We are able to answer eight out of 16 calls. Since our new hotline allows for detailed evaluations, we can later determine that almost all callers "gave up" after less than a minute. We cannot determine whether this is due to our otherwise (even) faster response times or because they checked our status page in the meantime, but our greeting definitely points this out. In any case, only one caller ended up on our voicemail, which in turn feeds directly into the ticket system. This is activated when no "real person" manages to answer the call within two and a half minutes.

1:37 p.m.:

No solution in sight – we continue to investigate the problem, now with several people, and find that although the (LACP) interfaces of all connected routers are up again, no "real" communication is possible. Simply put, but no less true for that: nothing within our iBGP network can be pinged. No router connected to these switches can reach another.

1:38:15 p.m.:

The first of our BGP sessions at DE-CIX come back online, once again creating the false hope that everything is now back to normal and that the issue only took a moment to resolve. At first glance, this assumption even seems plausible, because we have configured an init-delay-time of 240 seconds in our MC-LAG configuration – which should actually only be relevant when rebooting a member, but you never know. Timing-wise, it would have fit, but let's not kid ourselves, we didn't check or recalculate it that precisely at the time.

1:43 p.m. – 1:48 p.m.:

We have to realize that nothing is catching on here. There is some traffic on the network (about 10% of the previous level), and we are seeing individual private peerings and transit customers back up again in addition to DE-CIX, but the majority is not recovering. At this point, it is not clear why this is the case. We now know.

As a last resort – and because it all smacks of a "bug", not because it would be logical – we delete all interfaces that have been reconfigured in the previous hours from the configuration of both switches. We also reset the port channel between the switches on which the ICCP is running (or rather, should be running). The logical interface still has full capacity (800G), no errors, no flapping – but the ICCP remains down, and the devices cannot even ping each other.

1:49 p.m. – 1:53 p.m.:

We must recognize that we are not getting anywhere like this. Time for an emergency reboot of both devices.

We have access to the serial interfaces (consoles) of all critical network devices in case of absolute emergency, including these switches. Before we trigger the reboot, let's make sure the access is working. Although we reach the devices wonderfully via SSH and actually only need the serial console when exactly that no longer works, not being "blind" when rebooting such critical infrastructure is more than reassuring and can significantly reduce downtime in the event of further errors.

As expected (and regularly proforma tested), our console access works.

1:53 p.m.:

The reboots are triggered. Exemplary of the second switch:

Oct 23 13:53:47 ca2.ix-fra8 mgd [7077]: UI_CMDLINE_READ_LINE: User 'root', command 'request system reboot '

Oct 23 13:53:48 ca2.ix-fra8 sysman [9242]: SYSTEM_REBOOT_EVENT: Reboot [system] [reboot] []

1:56 p.m.:

The switches come back online one after the other, first ca1 (because restarted earlier), then ca2.

Oct 23 13:56:50 ca2.ix-fra8 eventd [10830]: SYSTEM_OPERATIONAL: System is operational

Since both members are freshly booted, they are waiting for the init-delay-time before the (logical) interfaces actually come up. It is intentionally configured in this way and complies with the Juniper recommendation to prevent a member from joining the service after rebooting before everything is actually started and "warm". An excruciating four minutes pass, during which at least the physical interfaces come online cleanly.

2:01:09 p.m.:

The last physical and logical interfaces are coming back online. The BGP sessions on all dataforest routers are already starting again, and traffic in the network is suddenly increasing.

2:02:22 p.m.:

All internal and external BGP sessions are online ("established").

2:03 p.m.:

We will report the restoration of availability to our network on our status page.

2:09 p.m.:

Our network is back to normal traffic levels.

Causes, unembellished

First of all, it's clear that the switches need a software update to eradicate the Junos bug. We did the last update in February and it is a bit bitter that the next one is already pending, but the error has just occurred. Until then, we will keep our hands off comparable configuration changes.

We remember that a few ports and BGP sessions came back up after a few minutes and made us believe that the interfaces flipped briefly and then recovered on their own. The subsequent analysis then shed light on the darkness very quickly, and the result is anything but complicated: Everything that started up again was attached to the switch ca1, whose l2ald — as described in the timeline — had not finally died, but had recovered. Perhaps it's slowly dawning on one or the other why we didn't restore our network with half bandwidth.

We previously looked at the log extract from a router where everything worked as it should and the split-brain situation was resolved within two seconds. Well, the simple truth is: that was a coincidence. Every connected device, every router belonging to our carriers that had to choose one of the two switches, made that decision at random. Our own routers did too. And in our case, everything that needs to be redundant is connected to both switches. This meant that a lot of decisions fell on switch ca2, and while it was absolutely unable to learn MAC addresses and thus enable the forwarding of productive traffic, it unfortunately appeared to be alive and well to the outside world. In short: this was a case that simply could no longer be handled with LACP in general and, unfortunately, with our MC-LAG in particular. After all, the ports were all there.

Our mistake in designing the POP was not taking such a specific error into account. The failure of any switch would not have caused an outage. Neither would a crash of the operating system, nor many other things. But the fact that a switch no longer learns MAC addresses while still speaking fluent Ethernet and, above all, LACP was too much.

Our mistake in the diagnosis, and thus not the cause of the malfunction, but of downtime that could have been shorter, was not to manually check the chassis alarms of the devices in question again because we relied on monitoring. This had worked, but the alert was not passed on internally.

We have drawn conclusions and lessons from both mistakes.

Action plan and timeline

Two bitter but necessary findings right from the start:

- Our Interxion PoP should not have failed due to a software error, but even if the Interxion PoP fails, this should not lead to a complete network failure. Until now, our network setup was not designed to cope with the entire PoP failing. It is clear that this is a weakness in the concept, and it was already apparent before. As some of our social media followers know, we moved into another data center, Equinix FR4, in July. What was actually supposed to be announced shortly in a more festive manner is now summarized here in a few sentences: With this data center, we are opening another dataforest PoP, which will offer full redundancy to our PoP at Interxion / Digital Realty in the future. Equinix is not yet fully integrated into our backbone, but the first 100G customer servers are already running there, and the fiber optics we have leased between Interxion and Equinix are already live and busily transporting traffic for you. The fact that our PoP failed before we were able to offer full redundancy with Equinix is doubly bitter, but it cannot be changed. (Due to its design, everything continued to run without failure at Equinix – since only a few customer projects are running there, we did not treat this separately on the status page, as it does not make much difference for 99% of our customers.)

- Ultimately, there is still a slight dependency between the devices in an MC-LAG setup. And there are obviously things that can go wrong. We have therefore decided to no longer use MC-LAG in our edge network. We will dismantle the existing setup piece by piece and eventually dissolve this MC-LAG cluster. From then on, the devices will run completely independently and will no longer be dependent on or wired to each other in any way. The necessary restructuring of the foundation of our edge network is no small feat, but it is the only logical consequence. This is made a little easier by the fact that internally (since we made ourselves "ready for Equinix") we no longer rely on large LACP channels via two switches, but instead implement load balancing and redundancy with ECMP. This is already the case with some upstreams (both private peerings and transits). But there is still a lot to be done. We will now have to migrate from LACP via two switches to individual ports, each with their own BGP sessions, in order to be able to work with ECMP there as well. So we are not giving up redundancy — we are just implementing it differently.

These findings also determine the key tasks for the near future, but there is still more to be done. Below, we provide an insight into what has already been achieved at the time of publication and what still lies ahead.

October 2025 (completed):

- Comprehensive analysis and clarification of the fault in order to fully understand it and to be able to derive measures

- Setting up necessary carriers and peerings in Equinix (to start: Tata, NTT, Cloudflare and Google)

- Connecting Interxion and Equinix sites via newly leased optical fibers

November 2025 (completed):

- Various monitoring adjustments:

- Alerts concerning critical switches must always be reported directly to the network department in addition to the regular on-call duty to prevent further delays in diagnosis. Previously, this was only the case for our routers, but it has now been extended to all core and aggregation switches at all locations.

- Our Observium monitors network devices via SNMP, which is relatively slow. As a result, we did not receive the alert for the chassis alarm, which has been known since 13:27:45, until 13:31. For the most critical devices, including those affected here, we have therefore also implemented their chassis alarms in our Grafana, where they are fetched by the junos_exporter every 30 seconds via a persistent SSH connection. These alerts are also sent to the on-call service and the network department at the same time — 24/7/365. As a result of these improvements, an alert would have been sent out directly to the right people at 1:28 p.m.. Whether this would have prevented an outage in its entirety is speculation, but within the realm of possibility. In any case, this would have reduced the time needed for debugging the issue.

- Connect firstcolo and Equinix sites to prepare for POP redundancy

- Developing the steps required for a rapid go-live of Equinix

- Proof of concept of a sustainable MPLS implementation in our network, to which all OSPF and iBGP sessions are to be migrated

December 2025 (work in progress):

- Contact all transit and peering partners to prepare for migration from LACP to ECMP

- Migration of remaining internal links from LACP to ECMP in order to dissolve the MC-LAG

- Implementation of a uniform ECMP load balancing policy within our network

- Prepare all routers and switches in the edge network for MPLS. In essence, this is an MTU adjustment on all interfaces involved. But since this is accompanied by a flap, we must cleanly migrate traffic down, make the switch, and migrate back before changing an interface to avoid (multiple) failures in parts of our network. We did that in the dataforest DNA written as a "zero-downtime principle", and we think that the benefit justifies the additional effort as long as it is practicable.

January 2026 (planned):

- Migration of all transits and peerings to ECMP to dissolve the MC-LAG

- Connect the maincubes and Equinix locations in preparation for PoP redundancy

- Migration of all OSPF and iBGP sessions to the new MPLS environment

- Full go-live of the new PoP by establishing full redundancy

February 2026 (planned):

- Dismantling of the MC-LAG

- Complete switchover to Equinix PoP so that various necessary maintenance tasks can be carried out on the Interxion PoP without risk. Of course, this also includes installing the software update that fixes the bug that caused the outage.

- Configuration of so-called BGP RIB sharding (BRS) on all routers to improve BGP convergence times. This makes it possible to fully restore availability more quickly after a router fails, regardless of whether it is from us or an upstream. This may require software updates, which we will announce in good time.

Responsibility, Guilt, and a Request

We are very grateful to have received encouraging feedback from many customers saying that we are not to blame for this bug. That is very kind of you, and it is true. However, as our customers, you do not have a contract with Juniper Networks, but with us. And it does not meet our own standards if our network – for whatever reason – fails almost completely. We would like to make a clear distinction here between blame and responsibility, and we bear responsibility for the "end product". Therefore, we are not simply chalking this up to "shit happens", updating the software, and continuing as before, but are considering what we could have done specifically to correctly intercept this type of error. In this case, a whole bag of measures has fallen out.

Of course, we also received negative feedback, a whole lot, actually. And we understand that such an outage is always bad. Nevertheless, in the face of various allegations, we must take the opportunity to clarify what can be expected of us — and what not:

Our network is designed for 99.98% annual average availability — that is our goal. And, to be honest, we have not lived up to that goal, because at the end of November last year, there was a problem due to a large-scale network attack, and the bottom line is that these two incidents left us with an unfortunate 99.98%. Contractually, we owe most of our customers "only" 99.9% on an annual average, although for most products this is of course based on more aspects than just network availability. And yes: everyone can expect significantly more than 99.9% network availability from us. We are doing everything realistic to get closer to 100%, but we cannot promise that there will never be another disruption. And that's why we don't. What we can promise is that we will deal with problems like this appropriately. That we will communicate what happened and derive improvements so that exactly the same mistake is not repeated. Nevertheless, anyone who needs (almost) 100% uptime must take matters into their own hands and not be dependent on a single provider. To the best of our knowledge, there is no web hosting company on this planet that offers 100% availability. So when (a few) individuals accuse us of costing them tens of thousands of euros due to a network disruption, we want to make it clear that the fault does not lie with us. We have been in the industry for over 15 years and can confidently say that we really go the extra mile for our customers. Not only in terms of availability, but also, for example, in terms of response times to disruptions, which are normally in the range of seconds, 24/7/365. We are probably the most annoyed when such disruptions occur despite all our precautions, but we cannot prevent them 100%.

We would also like to address the "demand" of some customers that all commits on our network devices should only be carried out at night. First of all: Our message on the status page ("major outage when we committed a regular change in our edge network") was not good. It led to misunderstandings; specifically, to the assumption that we had deployed some kind of risky major change in the middle of the day. We never do that: if we see a risk somewhere (i.e., if we can foresee that something could theoretically happen), we announce the corresponding maintenance work on our status page. But if we expect zero impact to the best of our knowledge and belief, we don't do that. Commits on our routers and switches are nothing unusual; they happen dozens of times every day. For the delivery of new servers, IP subnets, BGP sessions, and so on. There is definitely something in between, and that includes many commits in the edge network where we say "nothing can happen, but the commit has time and we'd rather do it late". That also happens several times a week – without any problems, otherwise we wouldn't do it.

In order to prepare our network for the integration of the Equinix POP, we have upgraded line cards, put several dark fibers and new upstreams into operation, migrated traffic to them, shut down other routes for maintenance purposes, and started implementing MPLS for the (modernized) networking of our locations and routers over the past few weeks. None of this caused any problems, and that was exactly our assumption with the commit in question. Unfortunately, the most ridiculous things happen where you least expect them. And that's despite the fact that 99% of our announced maintenance runs so smoothly and according to plan that we sometimes worry about engaging in unnecessary "overcommunication" with maintenance announcements.

Finally, it's important to remember that we now serve customers all over the world – what is nighttime for some is primetime for others. Network disruptions are therefore always very inconvenient and must always be avoided, and if we are unable to do so, we must deal with them accordingly. As we did here. We will not stop learning from our mistakes and minimizing them, but we do not want to raise unrealistic hopes for 100% uptime. With a little wink: Even the world's largest cloud and CDN providers have not been completely failure-free in recent weeks – and that's perfectly fine.